Klezmer

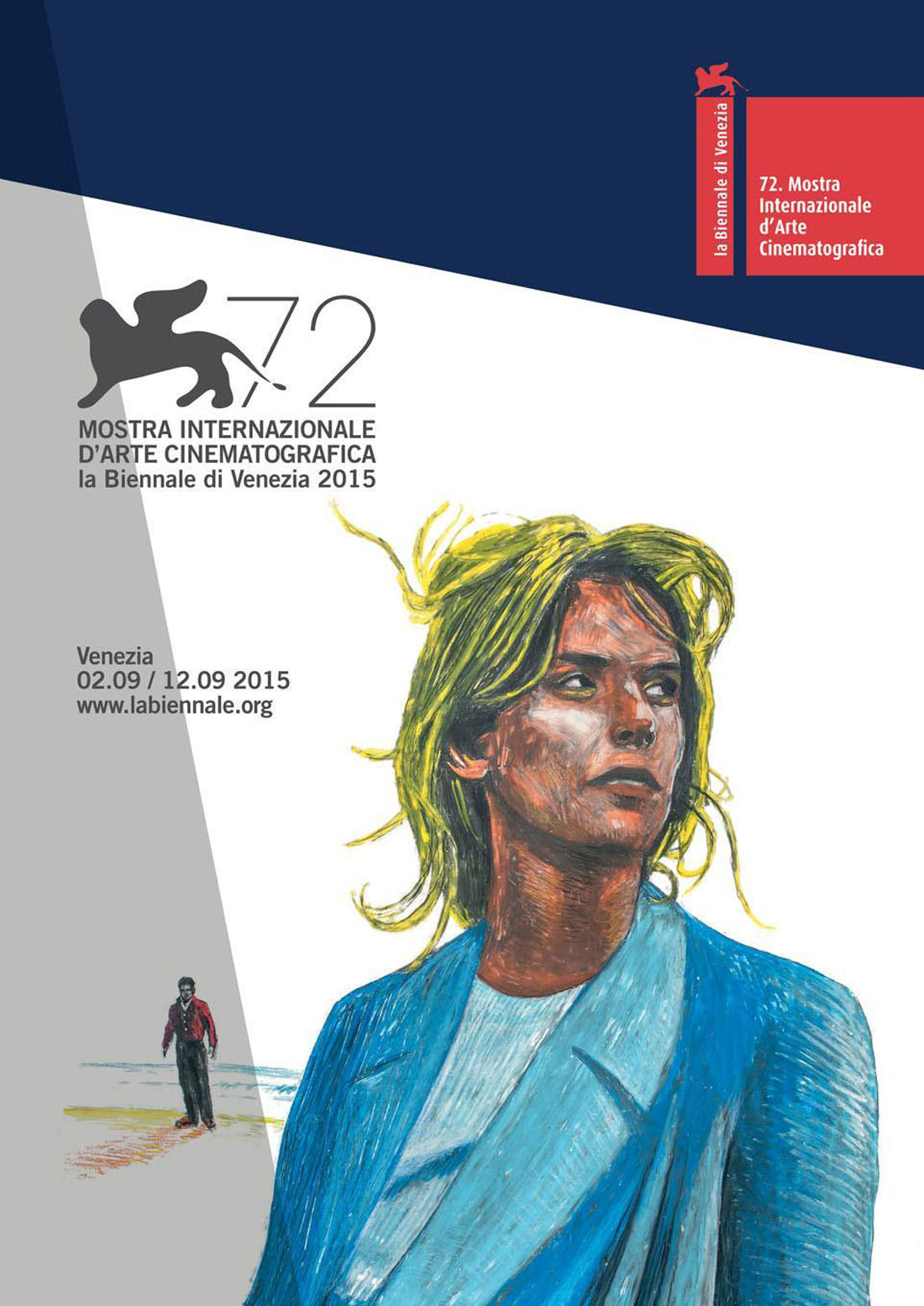

Piotr Chrzan ha scritto e diretto Klezmer. Il film viene presentato oggi 9 settembre alle 16.30 alla Sala Perla in concorso nella sezione delle Giornate degli Autori.

La traduzione in italiano dell’intervista è QUI: SCRITTORI A VENEZIA. Piotr Chrzan _090515

Piotr, can you pitch your film for us? Please tell us your story in a few lines…

Polish countryside, 1943. A group of young people finds a wounded man in the forest. They come to the conclusion that he is a Jew… In Poland only recently have books and publications (of the Polish Center for Holocaust Research based in Warsaw) become available, which make it possible to imagine, how these young people could behave in such a situation and what “options” were imposed on them with the reward and punishment system created by the German occupant. Therefore the story presented in Klezmer is a story previously never told – and I believe that this alone makes it worth telling.

How did you come up with this idea?

I have been dealing with the subject of the Holocaust and issues connected with life in the Polish countryside under German occupation for years. In fact I’ve been dealing with these issues since I was a child, when I heard the first “wartime stories” told by the seniors living in my village. Sometimes in these stories these two subjects intertwined. So the idea for this film has always been with me.

More than seventy years after the Nazi occupation, the film industry keeps producing important movies about that tragic time of humanity. Do you think that we constantly need to remember because certain issues (like racism, intolerance, violence, etc.) are still urgent and actual?

I’m afraid that the educational power of films is very limited, especially of those who deliberately strive to promote positive types of behavior and condemn those that are negative. Unless one is making such films within a totalitarian system. Then they reach audiences already pervaded with proper ideology and they can truly effectively strengthen certain behavior types within the society, desired by the authorities. Regardless of these reservations I believe that it’s worth it to make films presenting the tragic time of humanity, maybe not so much out of a need to remember, but out of a need to know. Perhaps the knowledge and awareness of what lies at the roots of racism and prejudice could to some degree limit their tragic effect on the perception of people of cultures, races or religions different than ours.

You wrote Klezmer on your own. Previously, you have co-written other works. How did it go all by yourself? Differences?

The differences are so fundamental that starting with Klezmer I have no intention to ever again co-write screenplays. I think that I write much better material when working alone, as I am in no way dependent on the imagination and ideas of co-writers.

This is your feature directing debut and is going to Venice. How do you see your future in this industry?

I hope that Venice illuminates my future in this industry with north Italian light and makes it possible for me to make films of my choosing.

The Polish film industry is one of the hottest in Europe right now. Why, according to you?

Probably as I am so close to the Polish film industry, I am unable to perceive it as one of the hottest in Europe, nevertheless I’m happy that from the European or world perspective the Polish film industry can be seen as such.

Which are the strongest points of your screenplay? Is there either a genre, a model, or an author that you felt inspired by in the writing process?

If I were to speak immodestly about the strong points of my screenplay, I think I’d have to mention those moments when the mood of the story dramatically, and at times radically, changes. These changes are caused by both new occurrences (e.g., discovery of a wounded man), and the appearance of new characters (e.g., of a girl that has a completely different view from the others on what should be done with the wounded man). As for the second question, I can’t point to any sources of inspiration that I am aware of. The same thing is true when it comes to sources of inspiration that I am not aware of, at least not without support of a good psychotherapist.

Which is your favorite scene? Why? What is it about?

If I had to point to just one scene, I’d choose the one with the spider. The two characters are playing with a spider – they seem to be completely detached from the wartime reality. Additionally, the male in the scene is a simple, country folk, poor boy, and the girl comes from a rich, educated Jewish family from the city.

What’s the main narrative theme of your story? How did you handle the theme, the characters, and their choices during your creative process?

The title Jewish character of my film, due to physical (he has been shot) and psychological (lost all hope of being rescued) exhaustion, is almost completely passive. Neither what he does nor says can have any influence on what the other characters in the movie do or decide. Such a dramatic setting of the initial situation (passivity of the character on whom all actions of the remaining characters concentrate) allowed me, among others, to show how the treatment of one person by another depends on the beliefs and ideas which were instilled in him or her. In Klezmer the characters carry within them a conception of a Jew, formed by Polish nationalist movements, the Catholic Church and folk superstitions. Klezmer shows how these conceptions and behaviors can present themselves in circumstances (war) which allow for their manifestation. Presenting how these mechanisms of social violence work is undoubtedly one of the main themes of Klezmer.

Relating to your second question, as I said earlier, it took me a long time to prepare for writing Klezmer. I familiarized myself with many reports from that time, so I believe that I had sufficient knowledge to create a proper setting for the story told in Klezmer as well as present the characters of the film in a balanced and believable manner.

Did you ever think of meeting some kind of target (read: audience) while writing Klezmer?

It took me just a month to write Klezmer, however it took me much long longer to prepare, although probably not as long as it took di Lampedusa to write The Leopard. After that not even a month passed before actor rehearsals, so I really didn’t have a chance to ask myself that question.

How many changes (if any) to the script, needed it to be made while filming? Did you ever feel sort of in conflict with your director-self?

A few changes were introduced, but not as a result of a filming necessity, but rather to lend a symbolic and metaphoric dimension to realistic scenes at the screenplay level. To answer your second question, there wasn’t really any conflict, with one of the reasons being that I directed the entire film in my head when writing the screenplay.

We founded the Writers Guild Italia two years ago in order to defend the Italian writers. What do you think about the work that the guilds do? Are you a member of a Polish writers association? How would you describe the working conditions for the writers and more generally the filmmakers in your country?

Unfortunately I don’t feel competent to answer this question. At present I’m not a member of any Polish writers association. And as I’m just at the beginning of my career as a writer and filmmaker, I hope that I will be able to share my views with you on the working conditions for writers and more generally the filmmakers in my country on the occasion of future Venice festivals.

Are there any Italian films that you considered pivotal during your artistic growth?

If I was to compile a list of countries with the largest number of films which influenced my artistic development, Italy would be at the top of such a list – I’m not quite sure which country would come in second. Therefore rather than naming all of the fantastic Italian accomplishments in the field of filmmaking I’ll just mention two titles, which I find to have much in common with my approach to presenting the subject of the Holocaust in films. These would be Benigni’s “Life is Beautiful” and de Sica’s “The Garden of the Finzi-Continis”. Why do I think so? Probably because I don’t like (and some I even hate) most Holocaust films. I think that from the aesthetic and moral point of view they pray on the subject too blatantly, unceremoniously and even vulgarly. However de Sica and Benigni tell their stories from a tragic time of humanity in a refined and subtle manner, yet with great power and clarity.

A recent Italian film or TV series which struck you in particular?

With TV Series it’s Gomorra. I can’t wait for the 2nd season to come out. With feature films I’d again have a problem (when it comes to Italian films, there are simply too many to choose from) with pointing to just one title, so I’ll indicate four: Paolo Virzì’s Human Capital, Alice Rohrwacher’s The Wonders, Giorgio Diritti’s The Man Who Will Come and the film version of Saviano’s book (I won’t mention The Great Beauty, as probably everyone does so). I can’t wait to find a moment to see My Mother. I’ll gladly allow myself to be stricken by my favorite director’s film.

How did you learn that your film had been selected for Venice? What are you expecting from the festival?

If I wasn’t bald, I’d probably be grey by now, because from the moment when my producer and I found out that Klezmer made the Venice Days short list, until the moment she shouted from the room next door (citing a letter from Venice): “Invited!”, many exceptionally long days had passed. And although I’m very nervous, I think I will survive the festival.

Le foto del film sono messe a disposizione della stampa dal sito della biennale.org, Le foto dell’autore sono sue.